What's in a Song: The Histories behind 5 Christmas Carols

We generally have a love-hate relationships with the streets at the time of year. It's nearing the end of December, which means carols and capitalism, often melting into each other in shops and shopping areas.

These days, the word "carol" synonymous with Christmas.

But it wasn't always this way. In medieval times they were mostly cicle dances that were secular or pagan in nature.

The word "Carol" then got co-opted into the Christian vernacular when the pagan festival of Saturnalia and the Christian celebration of Christmas were merged, making most carols Christian in context since then.

The original circle-dance carols fell out of favour in the 17th Century, only experiencing a revival in the 18th century, during the Victorian era which was also when most modern carols we're familiar with were written. Orchestras and choirs were set up one after another in England and the people needed songs to sing, leading to a Christmas Carol boom.

Besides having a long, storied past, Christmas Carols are curious windows into the history of European music: An indication of the singing and composition styles that were in vogue at the time. There are plenty of instances of "translated songs" where an English or American writer took a European dance or folk tune and filled it in with his own English lyrics.

1. Joy to The World

Joy To The World is a popular Christmas carol that was not.

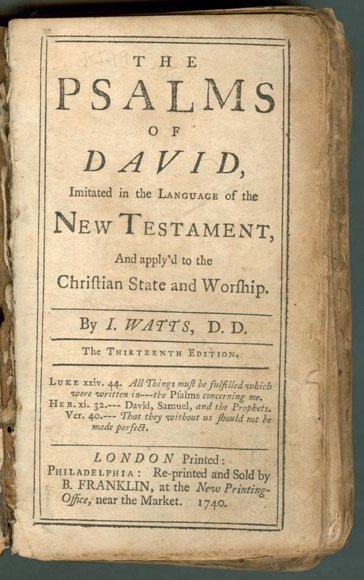

It was originally a poem simplified from Psalm 98. It was written and published in 1917 by Isaac Watts and was meant to be about the world celebrating the second coming of Jesus.

Watts was a minister and hymn writer. He was big on simplifying long, convoluted biblical texts for the everyman: Where religion during the time stipulated Psalms had to be sung unabridged because they were holy in origin—Watts found them to be boring, dreary and notoriously hard to sing.

He once observed, “To see the dull indifference, that sits upon the faces of a whole assembly, while the psalm is upon their lips, might even tempt a charitable observer to suspect the fervency of their inward religion." He sought to change this status quo through his poetry

Watt's Psalm-Poetry collection: The Psalms of David Imitated in the Language of the New Testament

It was only a hundred years later in 1839 when the tune "Antioch" was added to the poem. Making it the ubiquitous carol we hear today.

That's not where the rabbit-hole ends though, the "Antioch" itself has a fair bit of interesting history. It originated from a piece called "Comfort ye and Ev'ry valley" written by Georg Friedrich Handel, of the Hallelujah Chorus fame, and further arranged by Lowell Mason, an American church composer.

You can hear "Comfort ye and Ev'ry Valley" here:

Can you pick up on the familiar leitmotif?

2. Deck The Halls

This tune originally came from "Nos Galan" or "New Years Eve" a Welsh song and circle dance celebrating the new year, that was until it was picked up my Timothy Oliphant, a scotsman who often wrote his own lyrical interpretations of foreign tunes.

Also known as, writing completely unrelated Engish words to fit into the tunes of foreign pieces, a practice that was trendy at the time.

The earliest manuscript for the tune was written in the early 18th century, although it is highly possible that the tune dates further back.

The "Original" lyrics of Nos Galan, with the more familiar Deck the Halls appended to the back

The roots of the iconic "Fa la la la la la" line also had circle dance origins. Dancers would usually form a circle surround a harpist, which would play as accompaniment as they sang and danced. With the harp's melody filling the gaps in between verses. In the event there was no musical accompaniment, dancers and singers would fill the gaps with repeated nonsense lines that eventually became an integral part of the song.

This original circle dance version was possibly secular, or even pagan in nature, a curious juxtaposition to the religious roots of modern Christmas culture.

3. Silent Night (Stille Nacht)

When Austrian Catholic Priest Joseph Mohr penned the poem "Stille Nacht" in 1816, no one expected it to become one of the most played, most recorded carols in the world. The first performance of the carol was born on the back of a river flooding, which damaged the church organ in Mohr's church just hours ahead of a Christmas mass. Desperate, Mohr took the poem to his friend, schoolmaster and organist Franz Xaver Gruber wrote the song to be played with a guitar accompaniment.

As for the spread of the song, one of the congregants that day loved the song so much that he took the composition home with him to the Ziller Valley, where he crossed paths with two band of travelling folk singers who wove the song into their repetoire and took it across Germany and later across the workd when one of these families, the Rainers, performed the song in front of d Franz I of Austria and Alexander I of Russia, as well as making the first performance of the song in the U.S., in New York City in 1839

And the rest, as they say. Is history

4. O Little Town of Bethlehem

This one started out simple, the rector of a Church in Philedelphia, Phillips Brooks, came back from a holiday in Israel and was inspired to write this verse. He then instructed the church organist Lewis Redner, to set it to music so it can be performed by the Children's Choir.

Now here's the kicker, many of us in SEA may have a pretty fixed idea of how this carol sounds like, something like this

O Little Town of Bethlehem (Redner Version)

Looking further into the history of this carol, though, we found not one, but a whopping three "official versions" of the tune, each with its own equally loyal, borderline fanatic following.

The second most common version after the Redner version is sung to the tune "Forest Green" and performed more in England.

It is also virtually unrecognisable to most of our ears.

O Little Town of Bethlehem, Forest Green

And another called Wengen, most famously performed in Cambridge.

O Little Town of Bethlehem, Wengen

And in every comment section beneath these videos, you'll find folks proclaiming that that was the version they've been brought up with, or the version they've learnt in school.

Where this writer has never listened to a lick of these two versions until today.

Mindblown.

5. Ding Dong Merrily on High

Ding Dong Merrily on High is another dance hit turned religious tune. It first appeared as a French, secular, circular (try saying that three times, really fast) dance tune called Branle de l'Official.

For a bit of context, a good modern equivalent would be if Darude-Sandstorm became the next big thing in religious music.

Sharing the same circle dance origins as Deck the Halls/ Nos Galan, the Branle de l'Official was suggested to have been an equa-opportunity communal dance in which servants and household staff participated. Something inferred from its name, with l'Official being the name of the household staff's common quarters.

Branle L'Official in a rendition closer to the original

The later English lyrics was added by George Ratcliff Woodward, an Anglican priest and writer with a fascination for the ringing of church bells, undoubtedly one of the inspirations behind this piece.

.

Celebrate Christmas with Project Perfection with our series of Christmas discounts!

Find them bundled up here: 12 Days of Christmas: A P/P Gift Guide for the Audiophile in your life